Insanity is Doing the Same Thing and Expecting the Same Result

Randomness, jokes, jabs, and memory

We are all familiar with the quip: Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result.

At first pass it looks reasonable: why do you keep banging your head against the wall hoping something good happens when you’ve seen there is no fruit here?

But the domains in which this thinking applies are remarkably narrow: Only for a deterministic and stationary system will this hold. That is, only for what is essentially a mathematical function; a mapping in which each input maps to one and only one output. Every time you put a specific thing in, you always get the same thing out.

Ask yourself, how typical is this in the real world?

Winning the lottery again and again

You go into the quickie-mart, you buy a $5 scratch ticket, you win $100. Should you play again? If the answer were yes, the ticket manufacturer would go out of business.

A bad decision remains a bad decision even when the immediate results are favorable.

In poker circles this is known as results-oriented betting, and it’s a huge amateur mistake. Even if the payout looks good immediately, repeating this behavior is a losing play. Your hand that happened to win the last round is still a bad hand.

Simply, randomness already throws a wrench in the quip. When there is uncertainty, doing the same thing can lead to many “different things”.

In the context of poker and scratch tickets the idea is that over a sufficient number of independent exposures to the same situation, the average result will not be in your favor. In the long term the negative expected value will be realized. A bad decision remains a bad decision.

But there is another, perhaps more important reason that doing the same thing over and over and expecting the same result is insanity.

Jokes and jabs that you remember

You walk into a bar, tell a joke, everyone laughs. You tell the joke again. People cringe.

This is not a consequence of randomness, it’s because everyone remembers the joke you just told. If you tell it one more time they’ll really think you’re insane, especially if you appear earnest while doing so. The two tellings of the joke are not experienced as independent events.

Of course, you might try the same joke in the bar down the street and get a laugh again — they don’t remember the punch line. The two tellings in this case would be independent.

When systems have memory, they can’t be modeled as a straightforward mathematical mapping. What comes out does not depend only on what goes in, but also on the internal state of the system which is affected by previous exposure.

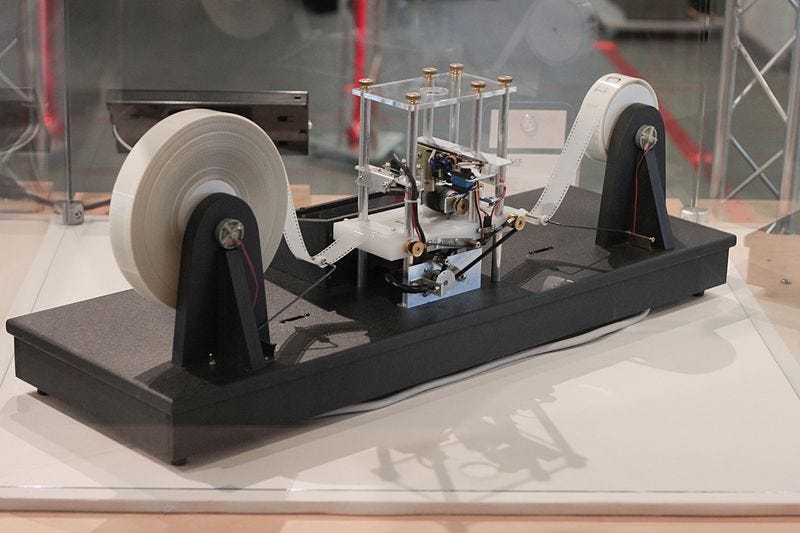

This is one of the virtues of computational paradigms: there is in principle no upper bound to the internal complexity of a computational system: a Turing Machine knows what to do next based on (1) its rules of operation, (2) the current input to the system, and (3) the current state of the system.

This is part of what makes it so difficult to treat computationally-rich systems in traditional reductionist ways: there is no straightforward input-output mapping. The internal “programs” play a causal role in how behavior unfolds.

Immunity to jokes and other things

Just as we become immune to a joke we have heard before, we can become immune to various pathogens for the same reason: our immune system remembers previous experiences and acts early to neutralize identified invaders. It also remembers how to respond to a particular invader.

And of course this is how vaccines are understood to work: give the immune system something to remember without exposing one’s body to the harm of a whole pathogen.

Two things to note:

(1) Given the computationally-rich and memoryful nature of the immune system, empiricism is our only guide when it comes to understanding possible risk and harm that could come from various events and interventions, to include repeat exposure to the same agent. Like telling the same joke twice, you can’t expect to have the same reactions — the events are best assumed to be non-independent.

(2) Memories of previous experience can also affect interactions with different agents in the future. When memory plays a strong role in system behavior, independence among any events is a dubious null hypothesis.

Knock knock, who’s there, banana, banana who

Knock knock, who’s there, banana, banana who

Knock knock, who’s there, orange, orange who,

Orange you glad I didn’t say banana?

When we form a memories we may also form certain expectations about what follows — this is why we need not only to remember, but to forget, because, as I am going on about, the same thing doesn’t always follow.

In the context of pathogen immunity, a problem that can arise from holding on to memories too tightly is sometimes called original antigenic sin. Simply, if your immune system is exposed to a new pathogen, but something about it reminds it of an old pathogen it seems, it can lead to an inappropriate immune response that isn’t tailored to this new agent.

This is just one example of how prediction becomes difficult when we must take into account future interactions with complex memoryful systems. In fact, the problem becomes essentially impossible to address with modeling: it is certainly infeasible and perhaps impossible to model all future environmental conditions and interactions.

Again, empiricism is our only guide here. When and where this will happen is subject to too much opacity, and too much computational complexity. The point here is we need to be cautious when projecting into the future with memoryful systems.

And we should be very careful in our modeling assumptions for such systems. For instance where we introduce probability distributions that depend on memoryless processes. Complex computational systems can behave in ways that aren’t reflected in tidy universal probability distributions. Complexity is messy. Precaution is warranted.

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you, it’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

Remember to go deeper

Memory is part of the beauty of living complexity. Reality has infinite depth, and so we must return again and again to experience the same things in new ways in order to go beyond scratching the surface.

This is in part what modernity has gotten so wrong about our relationship with the Earth: We have massively undervalued staying put. Staying put gives us the opportunity to experience the same place over and over, and on each encounter to go deeper, having gained the ability to navigate the coarser aspects of a place to get deeper into its subtle details.

This is why a good book can and should be read again periodically. This is why there is a difference between friends and strangers. This is what we have lost in interacting regularly with out neighbors.

Doing the same thing and expecting the same result is insanity: we live in a complex and rich world, full of memory.